Can Cognitive Behavioural Therapy treat Insomnia?

January 13, 2015

CBT for Insomnia – Session Protocol

February 25, 2015CBT for Insomnia – What Techniques can be used?

An Introduction

A number of CBT’s tenants, including the behavioural, the cognitive and the psycho-educational approaches, can be used to address the different aspects of insomnia; different techniques have been shown in various studies to be useful, and a protocol that encompasses these techniques, known as Cognitive Behaviour therapy for Insomnia (CBTi) has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of insomnia. The techniques of CBTi will be elaborated upon below.

Relaxation

This is the most commonly used non-pharmacological treatment for insomnia, since early studies had suggested a link between excessive levels of physiological activation and insomnia. The techniques which are used to bring about physiological relaxation include progressive muscle relaxation, autogenic training and biofeedback, and are especially useful in cases of initial insomnia. Other types of relaxation techniques have been found to be beneficial in decreasing another form of arousal; cognitive arousal. Imagery training, meditation, and thought stopping are some of the methods used in such cases. In fact, according to a number of authors, any relaxation technique should involve cognitive mechanisms, aimed at decreasing or calming the cognitive activity that occurs before sleep and encouraging a more positive outlook.

Sleep Hygiene

External factors may play an important role in sleep disorders, and sleep hygiene involves educating patients who suffer from insomnia to recognise these factors and then using behavioural modification, to eliminate or minimise them. A number of endogenous (related to lifestyle) and exogenous (related to the environment) factors have been identified; these can be assessed using the Sleep Hygiene Practice Scale, which identifies the problems contributing to poor sleep hygiene and provides an estimate of the patient's understanding about these factors.

Sleep Scheduling

Together with relaxation techniques and sleep hygiene, sleep scheduling strictly forms part of the behavioural model of the treatment of insomnia. The creation of a sleep diary is the first essential step in order to verify the style and habits of the patient, and allows the therapist to determine both the severity of the disorder as well as to monitor the progress of treatment. Interestingly, a number of studies showed a significant improvement in sleep just by asking patients to keep such a diary; a phenomenon coined the "sleep diary effect". It has been suggested that this effect is due to the fact that on the one hand, an increased awareness of sleep patterns reduced the anxiety related to sleep, and on the other hand, simply keeping a sleep diary could help overcome memory errors when it comes to estimating the average sleep time and therefore decreasing the perception of having slept too little.

Stimulus Control

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends this technique as a standard non-pharmacological treatment for insomnia. Stimulus control involves the attempt to re-associate the bed and bedroom with sleep, and to re-establish a regular sleep-wake schedule. Although sleep disorders may be caused by factors such as stress or illness, insomnia in its purest form is usually the result of a maladaptive behaviour that is perpetuated beyond the precipitating event. Many times, a person with insomnia no longer responds to the typical stimuli of sleep with tiredness and the need to sleep, but instead associates these stimuli with being awake. A questionnaire which can be useful for the evaluation of sleep-related behaviours is The Sleep Behaviour Self-Rating Scale.

Stimulus control consists of five simple steps:

1. Going to bed only when tired. People with insomnia often go to bed before they feel tired in order to increase the possibility of being asleep at the desired time. However, the greater amount of time spent in bed serves only to increase their psychological activation, causing more intrusive thoughts, worry and frustration with the inability to sleep.

2. Using the bed and bedroom only for sleeping. When the bedroom or the bed is used for reading, eating, watching television, or other activities, the environment becomes associated with staying awake rather than sleeping. The lack of association between stimulus and response (bed = sleep) may be particularly prevalent in older adults who spend a considerable amount of time in bed due to illness or physical restrictions.

3. Getting out of bed if you are unable to sleep. If the patient is unable to fall asleep after 15 minutes in bed, they are to go to another room and carry out some quiet activities (e.g. reading, watching TV, listening to the radio). This statement is also valid for awakenings during the night. When the patient feels sleepy again, they should go back to bed, but if they still do not fall asleep within 15 minutes, they should get up again.

4. Getting up at the same time every morning. Waking up on a regular basis, at the same time, helps restore and re-synchronize the circadian rhythms. Regardless of the amount of sleep that people who suffer from insomnia are able to get during the night, they should keep to the regular waking time throughout the week, including weekends.

5. Not taking naps during the day. Although daytime naps may seem like a good way to catch up on sleep lost during the night, in reality, they only serve to perpetuate the irregular rhythm of the circadian cycle, making it difficult for patients to fall asleep at the desired time.

Sleep Restriction

This technique is also indicated by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines for the treatment of insomnia. This method limits the ratio between time spent in bed and time spent asleep, creating a temporary and mild sleep deprivation. The function of this technique is to reset the body’s circadian rhythm, by reinforcing its homeostatic regulation, and which results in a more rapid onset of sleep, greater continuity and better quality of sleep. The method consists in asking the patient (who suffers from insomnia and usually stays in bed for eight hours a night, but sleeps only six hours, as derived from their sleep diary), to limit the time spent in bed to six hours; a time period called the "sleep window." This time window is then modified according to the weekly sleep efficiency achieved. The ultimate goal of sleep restriction is to achieve a sleep efficiency of 85%. Once sleep efficiency becomes higher than 90% the patient may spend another 15 or 20 minutes in bed per night. On the other hand, if sleep efficiency is of less than 80%, further restriction of time spent in bed will be applied. Since daytime sleepiness can be a side effect of sleep restriction, the window of sleep should never be less than five hours per night, regardless of the sleep efficiency.

Cognitive Restructuring

As described above, maladaptive behaviours are known to perpetuate insomnia. However these behaviours are usually supported by a number of false beliefs and unrealistic expectations about sleep which must be addressed. It is important that the therapist provides an explanation of how cognitive factors may influence insomnia, and illustrates how the personal interpretation and judgment of a situation can modulate emotional response. Dysfunctional automatic thoughts should be identified together with their underlying rules, attitudes, assumptions and core beliefs. Very often people who suffer from insomnia tend to report more negative thoughts about sleep as well as other areas such as health, work and family, both in period before going to sleep and during the night-time awakenings. Insomniacs also tend to engage in self-monitoring behaviours, frequently checking the time and their bodily sensations, as well as carrying out protective behaviours, such as checking how much time remains for sleep.

Cognitive restructuring is usually a longer process than the behavioural interventions, but it is crucial for effective treatment of insomnia. After identifying dysfunctional thoughts and attitudes toward sleep, the therapist helps the patient to recognise their lack of accuracy, to identify their maladaptive notions on sleep, and offers alternative interpretations to the patient, so that they can start to think about their insomnia in a different way, thus reinforcing the patient’s feeling of being able to control the difficulties associated with insomnia and the daytime consequences. The main goal of cognitive therapy is to guide the patient in considering insomnia and its consequences in a more realistic and rational manner, and can be divided into sub-objectives, which are related and complementary to each other.

First, the treatment should counteract misconceptions about the causes of insomnia. Many patients attribute their insomnia to triggers or specific stressors, such as pain related to a disease, allergies, age, depression, job change, separation, or bereavement. The patient therefore believes that these conditions should be fixed before their insomnia can disappear. Although these factors are often involved in sleep disorders, insomnia attributed only to these causes is counterproductive, because the patient may have little control over them. If a person interprets insomnia as a lack of control, they will begins to monitor their lack of sleep and worry about the consequences, fuelling the vicious cycle of insomnia; a chain reaction that leads to a state of physiological and emotional hyper-vigilance.

In order to help the patient become more aware of their negative automatic thoughts about insomnia, they can be taught to use the ABC model, recording their daily thoughts about sleep and insomnia and the emotions associated with them. To discover beliefs held about sleep, one may also utilise the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale. In order to identify the intrusive thoughts that occur, one may use the Glasgow Content of Thoughts Inventory, GCTI, which explores the ruminations of the patient before sleeping. Once thoughts and beliefs have been identified cognitive restructuring may commence. This involves a number of techniques which may include “Advantages and Disadvantages”, “Evidence For and Against”, “Cognitive Continuum”, “Historical Personal Contract”, “Behavioural Experiments”, “Percentage Pie Charts” and “Acting as if”. In general, it is seen that cognitive therapy for insomnia helps to change the basic ideas that perpetuate the problem of insomnia, and patients with insomnia should learn a number of basic cognitive strategies which include: having realistic expectations, not blaming insomnia for all their problems, not giving too much importance to sleep, not catastrophising after a night of little sleep, and developing tolerance to the effects of insomnia.

Putting it all together

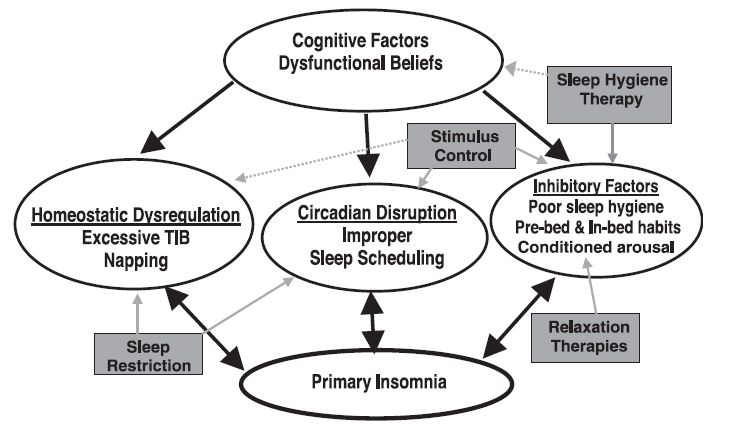

The figure below summarizes the causes that lead to or maintain insomnia, and the various strategies which may be adopted in CBT: