Suicide – Is CBT the answer? A practical look at CBT

September 1, 2014

What is Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)?

September 22, 2014Introduction

Health care rationing refers to mechanisms that are used to allocate health care resources. In technical terms, rationing can be defined as any mechanism that allows patients to go without beneficial services and may be either implicit or explicit. Over the last few years, we have seen a gradual shift from implicit to explicit rationing.

Advantages of explicit rationing within the NHS

The shift from implicit to explicit rationing has brought with it a number of advantages, which include:

1. Neutrality - The cornerstone of liberal thought; neutrality is easier to achieve in a health care system which makes it clear to one and all how services are going to be distributed. Explicit rationing might favour a decrease in political corruption and therefore leaves less space for conspiracy theories.

2. Suited to the current economic climate - The NHS is feeling the brunt of the current climate of economic uncertainty. In such complex situations, a system of health care rationing based on explicit mechanisms will offer clearer and less ambiguous paths towards achieving stated objectives.

3. Stronger public input - The public has a greater say in how health care resources are directed if the system is based on explicit rationing, leading to a better relationship between the NHS and the public.

How about the disadvantages?

1. Minorities may be disadvantaged - In such a system where open debate is present; there is a risk of the public disadvantaging minorities, such as the elderly or certain ethnic groups. On the other-hand there is also the possibility that minority groups may hold the system at ransom. Therefore the system is heavily dependent on included groups in decision making.

2. Weakening resolve of NHS and healthcare practitioners - By placing too much power in the hands of the public, the NHS may lose its ability to exercise certain fundamental control over healthcare policy and delivery, whilst healthcare practitioners might lose control over certain aspects of patient care.

3. Rigidity - A structured, mechanistic approach leaves little room for flexibility and judgement of situations on an individual basis.

The Elderly

One group of patients that have been in the spot light of this debate are the elderly, since as we age, we become more prone to chronic illness and longer term incapacities. The perception of the elderly as a drain on societal resources is supported by evidence of the high proportion of health expenditure devoted to their care (Dey & Fraser, 2000): “It is especially questioned where heroic but high cost and ultimately futile medical interventions are seen as marginally prolonging life without regard to quality.” However it is not just a question of efficiency but also of equity. The argument rests on the fact that resources are limited, and it costs exponentially more to prolong the life of an elderly person by a few years than it would to allow a young person to enjoy a full and healthy life. Williams in fact states: “Therefore, health interventions should be redistributed to the young to equalize ‘lifetime experiences of health’.” However this is easier said than done. I ask myself the question whether we are justified to view human life in terms of opportunity cost.

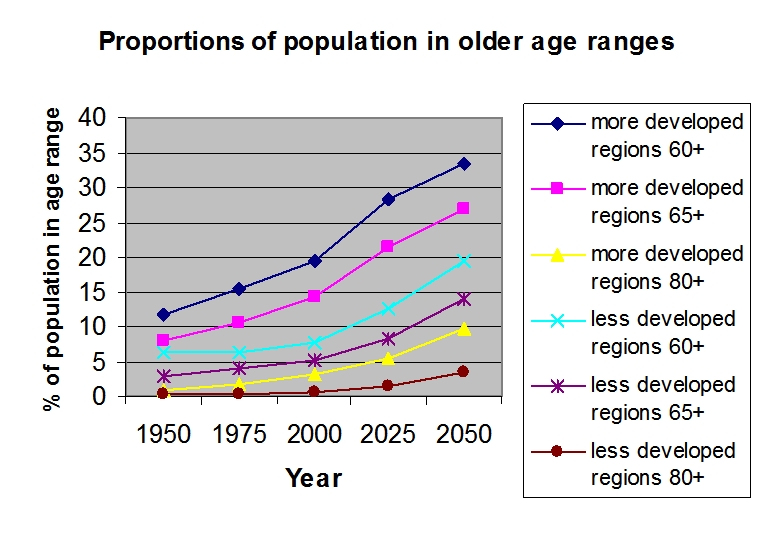

Projections of population ageing in developed and less developed nations - Impact more significant in many developing nations as ‘hourglass’ effect- middle aged people ‘missing’ from society due to AIDS/ travel abroad for work

Harmful Lifestyles

Other patient groups which receive much focus when discussing healthcare limitation are those who inflict damage ‘upon themselves’ and are then a greater burden on the health care system. These include smokers, drug addicts, and people who are obese, to name but a few. Taking smokers as an example, studies have shown clear links between smoking and a infinite range of medical conditions, from heart disease to impotence, from cancer to respiratory pathologies. There is a vast array of information available on the harm that smoking causes and it is easily available to one and all, and yet people insist on smoking, with clear risk of damaging their health. The end result is that the health care system is burdened by the ‘selfishness’ of individuals who carried out an activity despite dogmatic proof of risk. I believe that in these cases health care should definitely be restricted.

What is the way forward?

Focusing on the elderly, on the one hand I believe that general policies should seek to reduce the dependence imposed by this patient group (for e.g. through the removal of incentives to early retirement and employment policies). On the other hand, one has to acknowledge the rights and expectations of the elderly (for e.g. their rights to dignity, choice, participation, through work, leisure, housing, transport, family and social capital) and how these factors affect the health care system. With regards to people who engage in harmful lifestyles, I believe that the problem should be targeted at the source; through educational campaigns, heavier taxation on goods and services whose use results in demonstrable health risks, tax incentives for people who do not smoke and who are not obese, as some examples.

Restricting access to healthcare is a very delicate issue with a number of moral and ethical implications. However, in an economic climate of uncertainty and more stringent control of state expenditures, it would be naive to imagine that health providers can go on offering unrestricted access to health care services. Therefore whilst in a perfect world, health care would remain freely accessible to all, I believe that given the current situation, certain restrictions should be put in place to allow future financial viability of the health care system.